Impact

App-based heart rhythm monitoring is becoming widespread, but Belgian SME, Fibricheck, is the first to validate its detection tech for the billion-plus people worldwide with sub-Saharan African heritage.

By Paul Tullis

Cardiac arrhythmia, defined as a heartbeat that is too fast, too slow, or irregular, will affect one in three people worldwide over the course of their lifetime, with many instances life-threatening. The prevalence of the most common form, atrial fibrillation, nearly doubled in the 2010s. The good news is that this is largely a result of longer life expectancy; the bad news is that many more people live with the condition undetected.

Fibricheck was invented to fix that problem. The father of CEO Lars Grieten suffered a stroke in 2013 due to an undetected arrhythmia. “The stroke would have been perfectly preventable if the arrhythmia were detected in time,” says Bieke Van Gorp, Grieten’s co-founder. In most cases, atrial fibrillation can be kept in check with medication.

But irregular heartbeats are not constant. To be detected, the patient must be in “a-fib” when in a doctor’s office and hooked up to an electrocardiogram, an expensive machine that measures electrical activity in the heart.

That is, until Fibricheck came along. Founded in 2014, it is the first smartphone app enabling regular and long-term heart rhythm screening to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Union’s Conformité Européenne system.

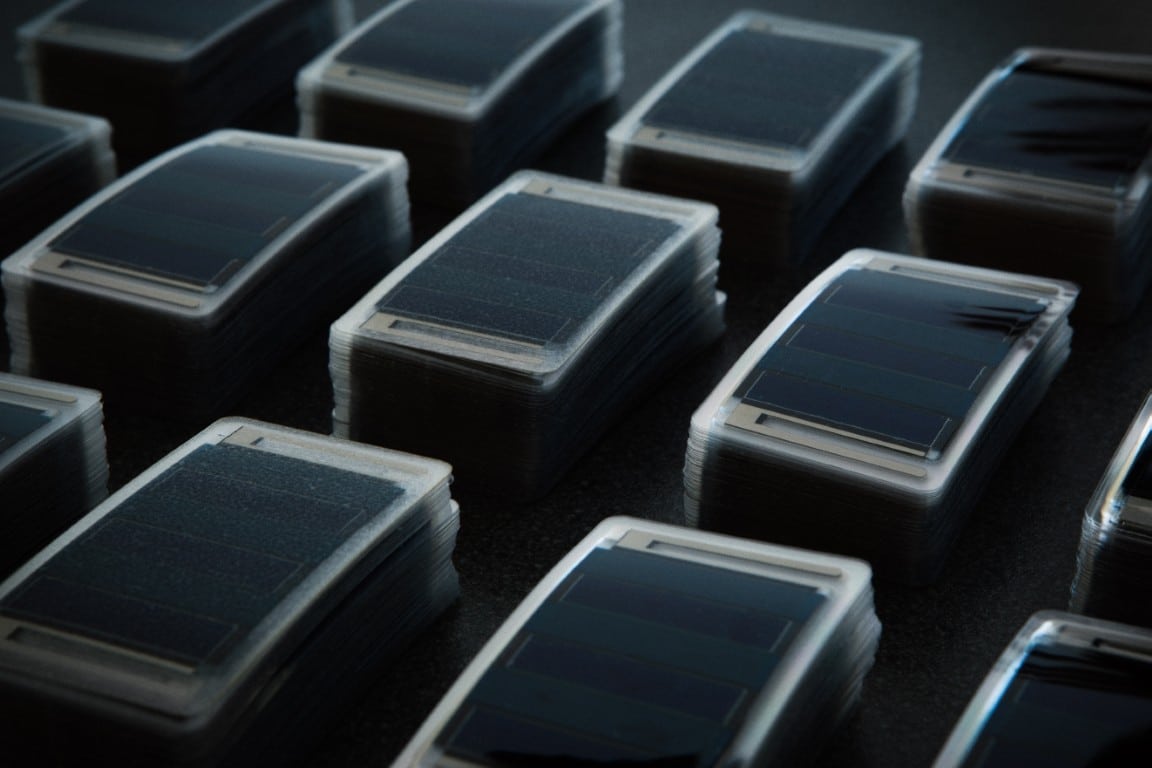

Fibricheck does this by leveraging a smartphone’s camera and flashlight to detect arrhythmia using photoplethysmography. When the heart beats, blood vessels momentarily expand, then contract. Photoplethysmography can monitor this process, and Fibricheck’s algorithm analyses the measurement, displays the results in graphs that can be interpreted by a physician, and delivers a report that is easily understandable by non-clinicians.

Fibricheck has now been clinically validated in more than 85 peer-reviewed publications, and used by more than one million people.

“We have proven that we are as good as echocardiogram devices in the doctor’s office, and even better than the Apple Watch electrocardiogram,” Van Gorp says.

However, it bothered Van Gorp that the technology had not been validated on people with darker skin tones, such as those with sub-Saharan African heritage. “Although we were very confident that Fibricheck would work perfectly on darker skin tones, for us, it was super important to confirm this,” Van Gorp says.

A partner of Fibricheck’s happened to be active in Nigeria, which made this African country the natural place to carry out international collaboration to validate the app. However, Nigeria had a difficult environment in which to conduct sophisticated medical testing, owing to the country’s poor infrastructure; cardiology even more so. Due to a brain drain of heart specialists to wealthier countries, there are just roughly 500 cardiologists in the country of 200 million, according to Fibricheck’s research.

“It was very challenging to arrange meetings with cardiologists within the healthcare system, and a lot of people are maybe not properly treated. There are long waits just because there is not enough capacity,” Van Gorp says.

A planned clinical study to record with Fibricheck and an electrocardiogram simultaneously needed to be moved to Belgium as a result, but a proof-of-concept evaluation went better than expected. The initial goal of 25 participants was almost doubled thanks to the efforts of partners at Mayriamville Specialist Hospital in Lagos.

“The Mayriamville team really went the extra mile and were super positive about the implementation,” Van Gorp says.

Forty-six patients used the Fibricheck app over seven days. Results demonstrated high effectiveness, with symptomatic patients regularly tracking their heart rhythms, indicating strong engagement. “They were surprised that it was so easy to measure,” Van Gorp says.

While Fibricheck performs as well or better than the Apple Watch, it has a major advantage, one which is especially valuable in lower-income markets such as Nigeria: far lower cost, because no additional device is needed. Smartphone penetration is around 85% in Nigeria, up to the age of about 80 or 85 (similar to Europe), Van Gorp says, which makes the product available to emerging markets where spending 300-700 euro on an additional wearable device is not an option.

Now, Fibricheck is focused on landing regulatory approval in Nigeria. With this already complete in so many markets (Australia, parts of the Middle East, and other regions, in addition to the United States and European Union), it is essentially a matter of filing existing documents.

Of course, Nigeria is only the most populous country in Africa, and there are nearly 500 million more people with dark skin tones south of the Sahara. “If we launch successfully in Nigeria, then we might look at other countries,” says Van Gorp.

In the meantime, people with darker skin tones in markets where Fibricheck is already approved have the assurance that this smartphone medical device will work as well for them as for anyone else.

“Our major goal was to make sure that the app works as well on darker skin tones as on lighter skin tones, and that has been successfully proven,” says Van Gorp. “Our primary focus is the timely detection of problems to avoid worsening outcomes, and to offer people peace of mind when they are unnecessarily worried about their heart health.”

Eureka programme and project name: Innowwide ZumaPulse

Countries involved: Belgium targeting Nigeria

Project execution: 2024

Got an innovative idea? Explore our funding opportunities designed to support groundbreaking projects and help turn your vision into reality.

Secure the resources you need to bring your ideas to life.

See all open calls